000013 On Hinton

AI inventor Geoffrey Hinton’s theory of consciousness or experience involves a refutation of an idea he refers to as the “theatre in the mind”, which—though he doesn’t put it this bluntly—means “experiences”. He thinks there is no such theatre, or in other words, there is no such thing as “experience”. You do not in fact have experiences, you do not see or hear anything. Hence, computers are like humans—neither has experiences or is conscious.

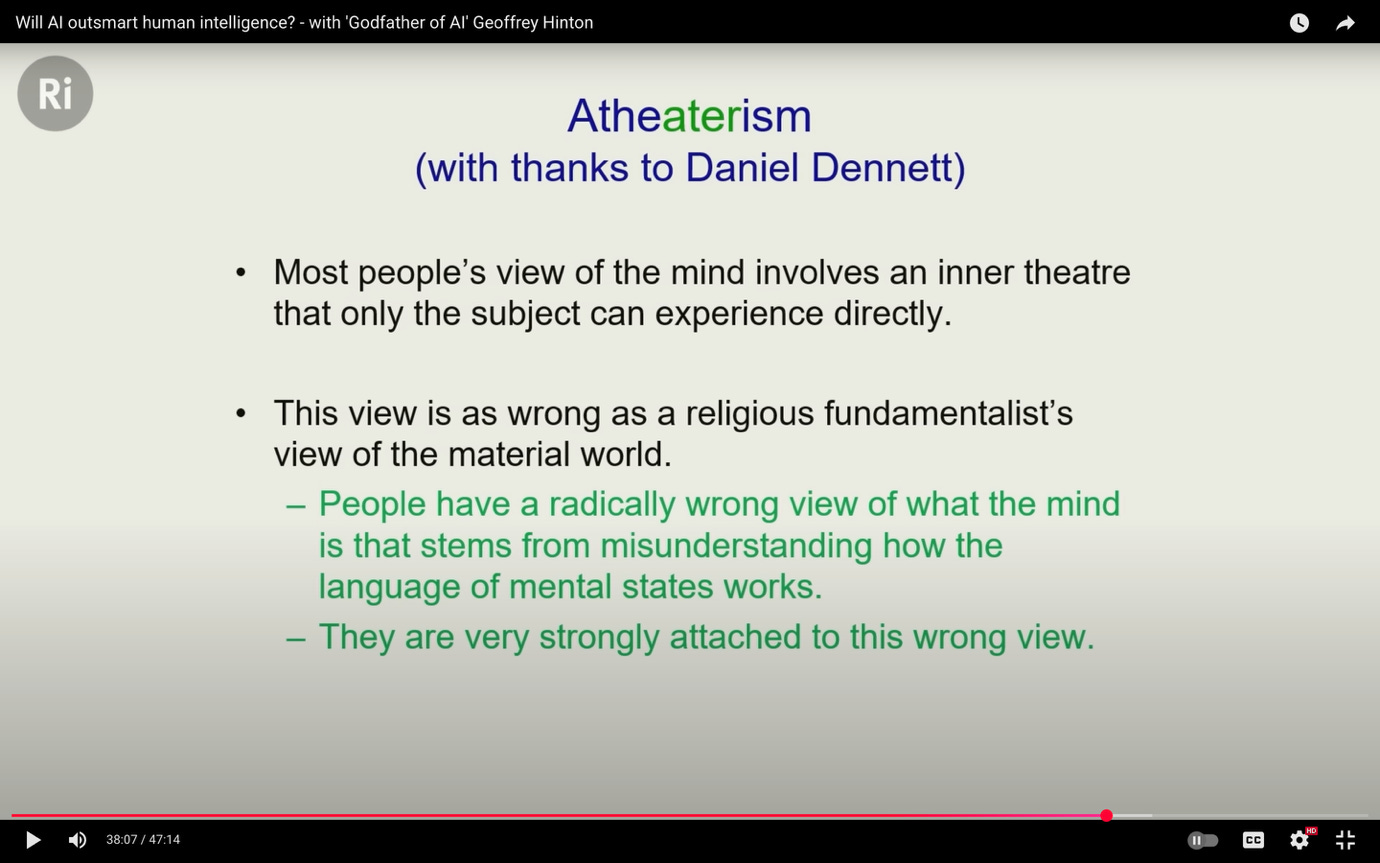

In a lecture uploaded to YouTube by The Royal Institution on 22 July 2025, the following slide appears (timestamp 38:00):

The slide has the heading “Atheaterism” and below it “with thanks to Daniel Dennett”. I have reviewed the philosopher Daniel Dennett’s book “Consciousness Explained” in a series of articles and shown the various insufficiencies in his theories. Hinton appears to repeat many of Dennett’s mistakes. For a more detailed analysis of those mistakes, the reader can take a look at my review of Dennett’s work.

In the absence of a more explicit or detailed explanation of what Hinton means when he talks about a theatre in the mind, I presume that his beliefs here are influenced by Dennett’s idea of “Descartes’ Theater”. For Dennett, Descartes’ Theater—an inner theatre in the mind—represents the idea that people have experiences. When you walk around the street, you see houses, trees, birds. When you have these experiences you are the observer in Descartes’ Theater. What you see on the metaphorical stage of the theatre is your experiences.

According to Dennett and Hinton, there is no such thing. There is no Descartes’ Theater. In other words, there are no experiences. When you walk around the street, you do not in fact see houses, trees, birds or anything.

With this view, it is easy to see how Hinton is able to believe that computers are like humans. Computers don’t experience anything, and humans don’t experience anything. They are the same.

I think Hinton is mistaken. For one thing, because I do see and hear and experience things. His beliefs fit in with views held by some philosophers, which I’ll touch on briefly in order to lay out the difficulties underlying Hinton’s claims.

They are the beliefs of a strain of philosophers who think that everything that is important or real about the mind is things that can be shown to others. This showing to others constitutes “proof” of the existence of something, for these philosophers. If no such proof can be produced, the alleged thing does not exist. So if I make the claim to you “I have an apple in my hand”, I can provide proof by stretching out my hand and showing you that I’m holding an apple. You can look at it and be satisfied that I’ve provided “proof”.

The problem is that no such proof can be presented for claims such as “I see the colour blue” or for any claim to experience. You might think you walk around the street and you see and hear things—you see people and houses and trees. But your experience—your seeing the people and houses and trees—you cannot hold that experience out before others like you can an apple in your hand and thus present proof to validate your claim “I have experiences”. For Dennett, Hinton and others, this inability to hold out “experience” before others means that there is no such thing as experience. Only what can be demonstrated according to their specific demands for proof can be considered “real”. You can’t demonstrate that you see or hear anything, therefore you do not see or hear anything. You do not have experiences.

Alongside their belief that only what can be demonstrated is real, they have the parallel belief that only what can be explicitly articulated in sentences is real. Perhaps these two beliefs more or less amount to the same. You can in a sense describe what you’re seeing when you say “I see a green apple in your hand” but you can’t describe “seeing green”. Or you can’t describe “seeing extension” i.e. seeing a table has length and width, though you know what extension is. This inability to describe such things means they—the experiences—don’t exist, for Hinton and Dennett. Rather, what exists is something like the statements. You say the statement “I see the table” or “I see a green apple” and your uttering those statements is the experience. Beyond the statements there is nothing. Only what can be articulated and thus in a sense demonstrated or communicated to others is real. (You might say the sentences out loud or internally to yourself in your mind.) And such things as consciousness must fit into this system of reality—consciousness in some way consists of things that can be demonstrated or articulated or maybe consists of the sentences themselves.

These beliefs perhaps make it easier to claim machines are conscious. As computer programs or their relevant output consist of statements and consciousness too consists of statements, computers can be conscious. For a machine and a thing to be conscious, then, is for it to make declarations like “I see the green apple”. Beyond this, there is no consciousness.

I don’t find such theories very persuasive. It’s true that I can never “demonstrate” to you that I experience or see green or anything at all. From that you might draw one of two conclusions: (1) you can conclude, like Hinton, that because there is no proof, there is no experience; or (2) you can conclude that you do in fact see and hear and rather demands for “proof” like Dennett’s and Hinton’s are misguided.

I’ve explored various angles of this discussion in my review of Dennett’s work, where I’ve also pointed out that these theorists have no explanation of how thoughts come into a person’s mind—which is a major flaw in their theories and alone is evidence enough that they have no grounds to claim computers can think or are conscious.

But such details are part of a discussion that takes longer than there is space for here. I have given the reader a brief overview of the sorts of theories that—apparently—lie behind Hinton’s belief that machines are conscious.

If the reader thinks that they see and hear nothing, they might agree with Hinton and can conclude that machines are just like humans. Neither sees or hears or experiences anything. They can with sincerity say “machines are conscious just as humans are”. What they mean is—neither humans nor machines are conscious.

.

.

.

In the next article we will look in more depth at some of Hinton’s claims regarding what he calls “subjective experience” (which for him oddly means “hallucination”), and we will see that while he asserts—in his words—“it’s perfectly reasonable to think that these things [computers] are conscious” (timestamp 45:20), he presents no evidence to support the claim.

As I haven’t found any written exposition of Hinton’s views (and ChatGPT says none exists), I draw from the lecture uploaded to YouTube by The Royal Institution on 22 July 2025, which seems to be one of the more comprehensive public accounts of his views on the question of whether computers have “subjective experience”.

The second article on Hinton’s claims is here.